- Categories

- random

BLOGROLLS

Each Master Takes The Same Path

The other week, Amazon published an article outlining how they moved one of their services from a “modern”, distributed, microserviced architecture into an monolithic design (if all these terms don’t make sense to you don’t worry - this isn’t a software-focused article). This was big news in the software architecture community. Amazon are the company who pioneered microservice architectures. If Amazon made a mistake picking a microservice architecture, and they are supposedly the best in the industry for this design, what hope do the rest of us have?

It was a good moment for me to reflect on the path to mastery and everything I’ve learnt in the areas I’ve focused on in my life. Those who obtain mastery of a domain - be that sport, business, art, or otherwise - all follow the same path on their journey which takes place over 4 stages:

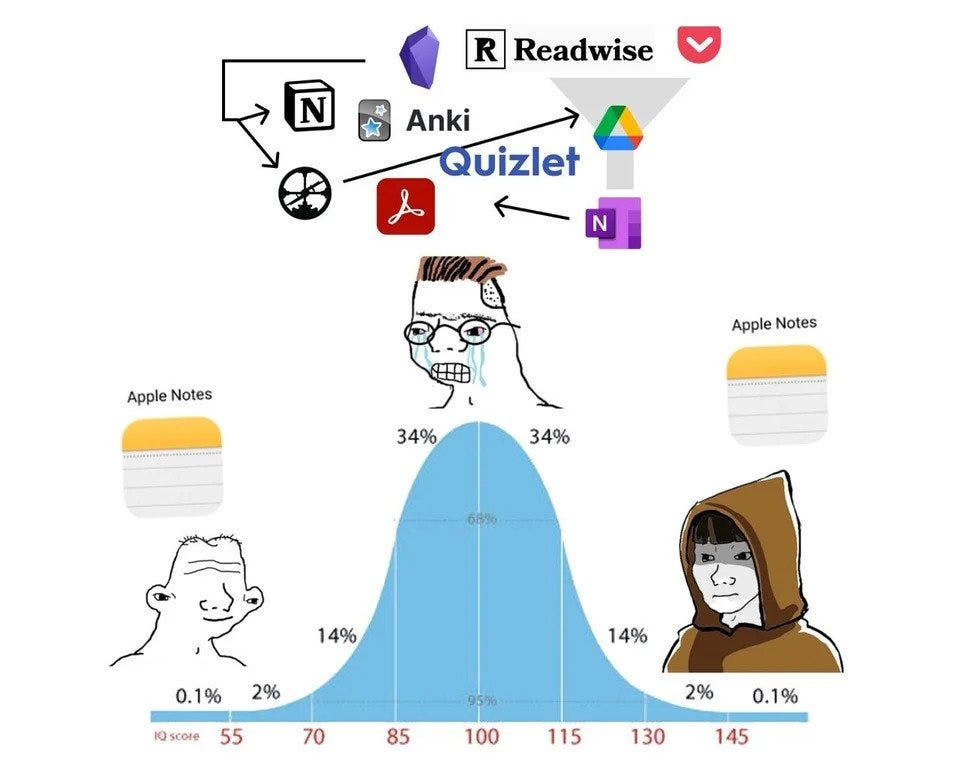

- You are an amateur. You do what comes naturally to you. Your technique and fundamentals are wrong, but you intuitively understand what needs to be done.

- You are a journeyman. You learn of all of the “best practices” and adopt and apply them blindly. You tune out your intuitive muscles and focus on trying to do what everyone else tells you do. As a result, you end up applying the wrong techniques at the wrong time.

- You become an expert. You are skilled enough to apply the “best practices” but can now discern when to use approach A over approach B. You tune back into your intuitive muscle and manage to make everything look effortless.

- Finally, as a master, you learn how to break the rules. You become the Picasso of your domain: you innovate, inspire, and influence your entire domain. This breaking of rules is intuitive too and taps into your initial raw talent you had during the first stage.

I believe this to be the case because of my prior experiences. I think two of these areas have had the clearest progression through this journey: chess and software engineering.

When I was a young adult I learnt how to play chess. When I was first getting started I had some intuition around the game: try to capture your opponents pieces so that they had fewer options, and try to protect your pieces such that any attack by the opposition would cause greater losses for them than they gained. Of course, I couldn’t *quite*** apply this intuition very well and managed to miss obvious traps, had pieces forked, and everything in between.

Eventually, as I got more into the game, I learnt all of the best practices taught online. I learnt what openings to play to respond to my opponent. I understood the value of pieces on the board and what a good exchange looked like. I knew all of the standard tactics to steal my opponents pieces. Although I never really got good enough to move into the 3rd and 4th stages, I saw these final stages in the chess masters I watched online.

These masters all knew what moves to place almost intuitively. They didn’t brute force search through every move combination: they could almost “sense” where the best moves were. They knew that certain moves would open ranks and files advantageously, how pushing a paws would change the dynamics of the match, and when a sacrifice of a bishop was justified. Only the best grandmasters however - Hikaru Nakamura, Magnus Carlson, etc. - somehow knew when to break the rules. They could see what no other player could see and sometimes what even a chess computer couldn’t see. A move that looked like a blunder to everyone spectating would materialise as being a brilliant strategic play 10 moves later. This is what differentiated them from the pack.

The domain where I truly felt like I was progressing through these stages was in my field of software engineering. When I first started programming in 2015, I was able to solve problems intuitively. I remember that the first two software products I developed were simple scripts to automatically solve analytical equations for my research group. They ended up saving hours of effort per week. It was terrible code and was impossible to maintain, but the solution was intuitively the easiest approach (run the script on your compute) and solved a legitimate problem for the research group (fitting curves manually).

Once I got my first software engineering role in an AI consulting firm, I started to consume educational material non-discriminately. I was learning about design patterns, industry best practices, and what “good” code looked like. I become dogmatic for AWS best practices: it should be serverless, infinitely scalable, and fully automated. I used OOP. I wrote unit tests for every function and class in my code. Worst of all I lost my intuition for why software was built in the first place: solving problems!

Ultimately, this meant that my designs were bloated and hard to work with, often requiring the skills of 3 engineers to maintain. They were all the “best practices” within the industry but the way they were applied did not consider the overall business context and resulted in subpar solutions for everyone involved.

I repeated these mistakes in my own firm for the first couple years of operations. Now, as I enter into my fourth year of operations, I feel like I am in the third stage of mastery. I now recognise what a simple solution looks like. I can cut away all of the excess in my designs to come up with a design that is business context-aware, addresses a legitimate problem, and doesn’t overengineer.

There is a long path forward for me to enter into the fourth stage of mastery. I am looking forward to the day were I can break the rules again. Maybe this time, however, it will be easier to maintain for everyone after me.

For any feedback or corrections, please write in to: Kale Miller